You call that a district?

|

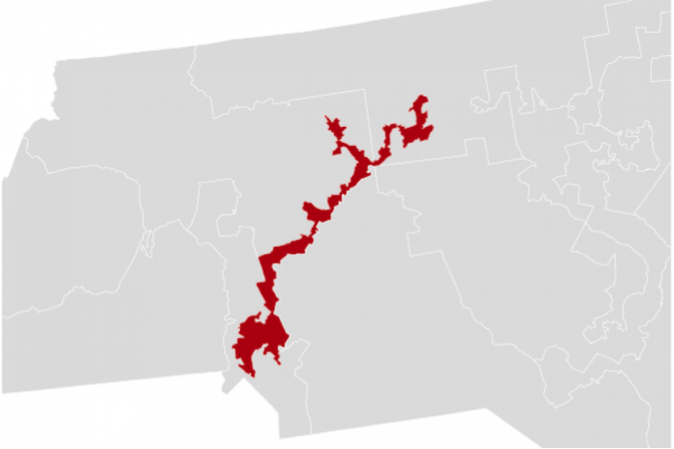

Below is an image of North Carolina’s newly drawn twelfth congressional district. At some points, it is hardly any wider than the interstate it more or less follows.

Why does it look like this? This spring, while speaking on the North Carolina House Floor, State Rep. David R. Lewis, the Republican chairman of the House redistricting committee, explained: “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map in a way to help foster what I think is better for the country.”

While North Carolina’s congressional redistricting proposals have made national news in recent months, Lewis’ comments are not the cause of the controversy (a federal court recently determined that the newly drawn first and twelfth districts unfairly target racial minorities — a trial regarding state-level boundaries began Monday). As long as partisan gerrymandering doesn’t target racial minorities and district level populations are distributed relatively equally, the winning “team” can, more or less, redraw the boundaries however it wants.

An analogy from another competitive domain, sports, might help demonstrate why this is flagrantly unfair.

Imagine (only for a moment, Duke fans!) the University of North Carolina men’s basketball team won the NCAA Championship game last week. And imagine that their status as the reigning champion enables them to re-evaluate and, if necessary, rewrite the rules for next year’s college basketball season.

What happens in our hypothetical scenario? With this rule-making authority, Carolina Coach Roy Williams decides to ban the three-point shot in 2016-2017.

What’s his justification for this change? For one, his team hasn’t been a particularly good from long-range in the past few seasons. But more importantly, Duke, Carolina’s arch-rival, has a number of good outside shooters. Banning the three-ball will put Duke at a decided disadvantage when matched up with Williams’ squad next year.

Given that Williams believes that it’s better for the game and the state if Carolina (a humble public institution) beats Duke (a privileged private university), he doesn’t apologize for making the rule change. Carolina, and all that it represents, should win; Williams sees his team’s victory as the triumph of good versus evil. Regardless, Williams knows that he better take advantage of this opportunity while he can — he’s sure Coach K would do the same if given the chance.

One can easily imagine the outrage that would follow. College basketball observers, not to mention the Cameron Crazies, would immediately cry foul. There’s nothing that incites us sports fans more than examples of patently unfair play (for example, a group of New England Patriots fans filed a lawsuit challenging the NFL’s removal of a Patriots draft pick following the ‘Deflategate’ scandal). Worse than that, in our thought experiment, Williams would not only have acted unfairly, but openly admitted to it!

As Rep. Lewis’ quote demonstrates, this hypothetical scenario matches the redistricting process quite nicely. In North Carolina, the team (political party) that wins the most recent contest (the election before redistricting) gets to set the rules for future competitions. And like Williams, party leaders do so in a way that benefits their “team.”

It seems pretty clear that this process is a problem if one cares about fair play. So what’s the solution? As Duke political scientist David Rohde has pointed out, the obvious answer, a “neutral” or bipartisan group of experts (like the NCAA rules committee) is not necessarily a good one. On the one hand, neutrality and bipartisanship are hard to come by in politics. On the other hand, even neutral or bipartisan committees can distort electoral outcomes at the district level.

Perhaps the resolution rests not in computer programs or technocrats, but in “the people” and their representatives. Democratic governance requires compromise in a large, diverse, political community, and institutional trickery cannot be substituted for what might be called “civic virtue.” It also requires a recognition that nobody can always have her way. Dadgum it, even ol’ Roy knows if we can’t agree to play by (relatively) fair rules, soon we might not be “playing” at all.

Isak Tranvik, from Minneapolis, is a graduate student in political science at Duke.

Want to stay informed on the go? Subscribe to our newsletter, This Week's 5 Gems. It's a curated digest of the week's top five stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Isak Tranvik

Isak Tranvik, from Minneapolis, is a graduate student in political science at Duke.

More Info